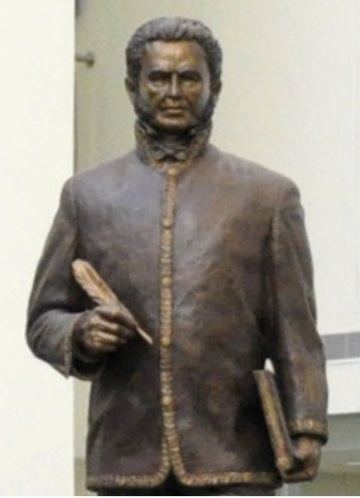

In 1811, idealist Revilla native Don José Bernardo Maximiliano Gutiérrez de Lara became dedicated to the Hidalgo Independence movement. Consequently he received the rank of Lt. Colonel in Hidalgo’s Army of the Americas and traveled to Washington, Baltimore and Philadelphia to enlist aid for his personal goals in the movement in Texas. In Washington and Philadelphia he met Caribbean adventurer José Alvarez de Toledo y Dubois who was a wanted man by Spanish authorities in Texas. Both on his exit and return trip through the Neutral Ground on the Texas-Louisiana border, he received sympathy and encouragement by numerous factions interested in Texas. In Natchitoches, Gutiérrez laid plans to invade Texas from the east. He enjoined another adventurer and former US Army Lieutenant Augustus William Magee to carry out the mission in the field. William Shaler, an American consul to Havana, Europe and Algiers and writer, also supported the two. It is believed that Shaler and indirectly Gutiérrez and Magee had the blessing of the American government as high as Secretary of State James Monroe, however, the official US stance after the invasion was disapproval. From their headquarters in the Neutral Ground, Gutiérrez and Magee openly advertised and assembled recruits from Louisiana with impunity for the Republican Army of the North and adopted the emerald green flag, possibly because of Bostonite Magee’s Irish background. Volunteers were offered forty dollars a month and a league of to-be-captured land. From San Antonio, Texas governor Salcedo followed the developments through his intelligence network and intensively tried to enlist more aid from his superiors and comrades in arms south of the Rio Grande to prepare for invasion and limit distribution of rebel propaganda. Governor Manuel Salcedo was continuously treated arrogantly by his distal and protocol-oriented bureaucratic uncle and Commandant Nemesio Salcedo. Either the latter did not clearly understand the mounting difficulties on the Texas border, or found them of low strategic priority. Nacogdoches commander Captain Montero, supported by subdeacon Juan Zambrano of Bexar, maintained their forces on high alert appealing to Gov. Salcedo for reinforcements. On 12 Aug 1812, the Republican Army of the North of about 150 men crossed the Sabine River and took Nacogdoches without resistance. Royalist Capt. Montero was unable to recruit a single civilian minuteman for the cause and as he retreated toward San Antonio, numerous members of his army and residents of East Texas joined the invaders. By late fall the Republican Army of the North controlled the area between the Sabine and Guadalupe Rivers. Lt. Col. Gutiérrez announced his intentions and appealed for popular support in the capital San Antonio:

“Soldiers and citizens of San Antonio de Bexar: It is more than a year since I left my country, during which time I have labored indefatigably for our good. I have overcome many difficulties, have made friends and have obtained means to aid us in throwing off the insulting yoke of the insolent despotism. Rise en masse, soldiers and citizens; unite in the holy cause of our country! I am now marching to your succor with a respectable force of American volunteers who have left their homes and families to take up our cause, to fight for our liberty. They are the free descendents of the men who fought for the independence of the United States; and as brothers and inhabitants of the same continent they have drawn their swords with a hearty good will in the defense of the cause of humanity; and in order to drive the tyrannous Europeans beyond the Atlantic.”

A complicating factor to both the rebel army and the royal government under Gov. Salcedo was the appearance of Dr. John Hamilton Robinson. Robinson was with Lt. Pike from the time he was arrested by Spanish forces near Santa Fé and his escort out of Texas to Louisiana. According to some historians, Robinson at the time was a British agent. Upon capture by rebel forces, it was learned that he had been sent by Secretary Monroe to meet Commandant Salcedo in Chihuahua to discuss problems on the eastern frontier and relay the sincerity of the US government “to cooperate with Spain in proper policing of the frontier.” Robinson was released when he promised to not reveal details of the rebel force and he was welcomed by Salcedo and Herrera in San Antonio, who were equally suspicious of Robinson and fearful of his learning their position, but wishing to learn of anything from his experience. After escorting Robinson on his way to the Rio Grande, Salcedo and Lt. Governor Muñoz de Echavarria deployed along the Guadalupe River east of San Antonio to meet the invading Republican Army. Learning of this, Gutiérrez and Magee turned south down the Guadalupe River valley, proceeded to La Bahia where they took control without much resistance, but where soon after Gov. Salcedo began a prolonged siege of the presidio where the rebels were grouped. Neither could budge the other and the stalemate was tying up meager forces on both sides. Finally a three day cease fire was called and Gov. Salcedo met with Col. Magee in reportedly a gentlemanly meeting with dinner and the trimmings. At the conclusion of the meeting Magee agreed to give up the fort for safe passage with provisions to the Sabine River. Part of the agreement was that Mexican insurgents in the Republican Army would be turned over to Gov. Salcedo, terms which were refused by the rank and file, both Anglo and Hispanic, the cease fire ended and the stalemate continued. In December, Col. Magee became ill and ineffective and died in Feb 1813. His death remains controversial among historians, some contending that it was a suicide. Col. Magee was later denounced by comrade-in-arms, Col.Gutiérrez:

“During this time [at La Bahia] we suffered every kind of calamity, the greatest of all being this: the American colonel Magee, who was my second in command, was a man of military genius but very cowardly; and moreover, he was a vile traitor in promising to sell me to Salcedo for fifteen thousand pesos and the position of colonel in the Royalist ranks. For this reason be was always opposed to my using strategy and other means by which I could have harmed the enemy greatly. But the divine Omnipotence, who always favored us, permitted this villain to fall sick and die, as a result of some poison, which he had taken to avoid being shot.”

Oddly enough, just when Magee died and the group at La Bahia was the most vulnerable, Gov. Salcedo and Col. Simón Herrera (Governor of Nuevo León and one time interim governor of Texas) lifted the siege and returned to San Antonio, the retreat giving cause for more royalist defections to the rebel cause. Commanded by Virginian Col. Samuel Kemper, who took over after Magee’s death, and buttressed by more recruits from the Neutral Ground and coastal Lipan and Tonkawa Indians, the Republican Army moved along the San Antonio River toward San Antonio where they were engaged by Col. Herrera’s royalist forces at Salado Creek. Col. Herrera’s army was routed in the engagement known as the Battle of Rosilla (also called Battle of Salado) at the expense of 330 men killed and 60 captured. As the Republican Army moved toward San Antonio, Gov. Salcedo composed a twelve point plan of honorable surrender and delivered it to Col. Gutiérrez who was camped at Mission Concepcion.

Capture and Execution of Royalist Gov. Salcedo. Gov. Salcedo and Col. Herrera dined with several of the Anglo officers the same evening and with dignity formally surrendered on the plaza in front of Casas Reales the next morning. Gov. Salcedo offered his sword in traditional ceremonial surrender to Anglo officers who suggested that he present to Col. Gutiérrez, their Commander-in-Chief. Apparently unwilling to make the offering to a rebel Hispanic, Salcedo instead plunged his sword into the ground. Gutiérrez released all rebel prisoners, formed a provisional government as governor and organized a tribunal, which found Salcedo and Herrera guilty of treason against the Hidalgo movement and condemned them to death. Anglo officers protested the decision and seemingly convinced self-appointed Governor and Generalissimo of the Republic Gutiérrez to spare them and send them to prison in southern Mexico or exile in Louisiana. The prisoners were placed under the escort of Mexican rebel Capt. Antonio Delgado and his company who the Americans believed were taking them to Matagorda Bay to sail for points south in Mexico or New Orleans. Delgado along with Pedro Prado and Francisco Ruiz of Alamo de Parras Company led them as far as Salado Creek about six miles outside San Antonio, site of the battle that that had occurred just several days before. There the rebel company ordered the prisoners to dismount, disrobe and after removing their valuables, the company slit the throats, and according to some, removed the tongue and beheaded Gov. Salcedo, Herrera and 12 others leaving them lying at the site without burial. Delgado returned to San Antonio boasting and joking of their butchery, which was announced publicly on military plaza.

The following is a document in the Lamar Papers labeled “1835, [M. B. LAMAR, SABINE RIVER]. INFORMATION FROM CAPT. GAINES.” In the document by James Gaines, a participant in the Gutiérrez-Magee Expedition, he describes the Nolan expedition, The Battle of Medina, about Lafitte, about Trespalacious and The Origin of the “Revon.” [Revolution] in Texas 1812. Notes in Lamar’s handwriting at the end of the treatise remark that the account is strikingly similar to one by Hall some 15 years afterwards.

Leave a Reply