After the Battle of Salado, we took possession of St Antonio 1st April 1813—at which time 1.4 Spanish officers surrendered without Battle, who were confined separately as crimnals; this was followed by another surrender on the same day, of 8 hundred soldiers & their officers, who joined the ranks of the patriots and took an oath to support the cause of the Revolution—On the 5the April the successful Patriots formed a new Govermt, Electing Bernardo Gutaris [Gutiérrez] Governor, an a council of 13 chosen out from among the inhabitants of the Town with the exception of two taken from the army, Americans by the names Masicote and Hale Several serious difficulties had arisen in the patriot army about trying prisoners; On their march from Labordee [La Bahia?] to St Antonio it was proposed by Capt. Gaines of the artillery, that in future to settle all further difficulty, the Mexicans should try the Mexican prisoners & the Americans should try the Americans taken. This agreement was drawn up in writing & signed.

A question now arose as to what disposition should be made of the 14 Prisoners who had surrendered themselves? It was determid by the Mexicans that they should be tried by a Court Martial & be shot; and for this purpose the court was accordingly organized—It was composed of the family of Monchacks [Manchaca] & their influnced. This family had been injured by these very men, and the result of court was a verdict of death. They were however affraid to carry the sentence into open execution, for fear of displeasing the Americans who the Mexicans knew to be averse to such a bloody and sanguinary course. Under the pretence of sending them to Matagorda with a view of shipping them thence to Mexico, the prisoners were taken out at night and their throats cut. When this was known to the patriot army, it created a sensation of general horror among the American portion of it, and came very near breaking up the whole army. The reader doubtless will feel on readig an account of it a similar horror. But this will be allaved on further development of facts.

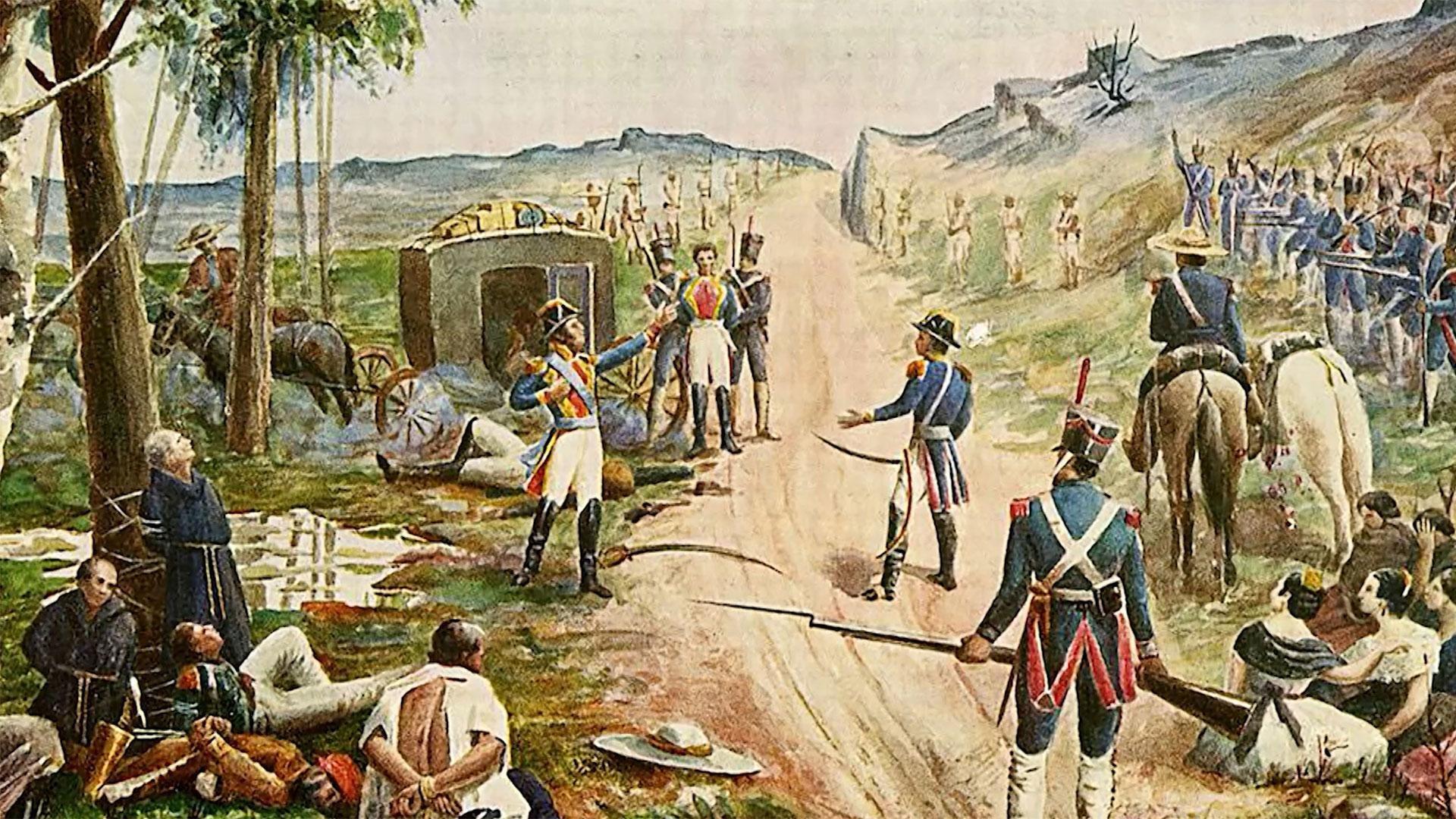

For the purpose of quieting the discontent which this seemingly cruel act had produced among the soldiers, Capt Gaines who was made familiar knowing to all the causes which induced and led to it was commission to make to the army the necessary explenation. The charges prefer against the 14 prisoners were their treachery to Hidalgo, Moncha and others whom they entrapped by villiany & murdered most inhumanly without trial or cause. The prisoners names were Salcedo the Govr. of Bexar, and Govr. A Herrero of the army, and Marcus and other officers Civil and military names not remenbrd. Monchack Lieut Sice, had gone to raise volunters for the patriotic army the former to Natchitoches and the latter to Nacogdoches. They had both succeeded in raising a large company, when the above criminals, Salcedo Herrero & others, induced them by bribery to abandon the cause; they accordigly let their men which they had raised & returned to St Antonio. On their arrival they were both taken up and publicly executed. Monchack head was exhibited publicly on the gate posts. His treachery deserved the fate he recd. But his family was now sitting in judgemt on these very men who had ordered the death of their relative—Their feeligs & their voice on the occasion may be easily known. This was one of the charges—on which they were tried; another Charge was their treachery & violence to Hidalgo—Hidalgo & Ryon the leadig patriots of the Revolution, had long been objects of terror & hatred. Salcedo, Herrera, and Marcus now formed a plan to destroy them. There was at Monoclover a patriot by the name of Elesondo, who was well known to Hidalgo & Ryon; He was bribed by Salcedo, & his associats to write on to Hidalgo to come on Texas; that his presence was wanted here. Hidalgo’s cause was prosperous in the Interior; every where he moved Crowds flocked to the standard. Elesondo wrote to him, that the people in Texas were a ripe for Revolution; that they only waited his presence to unite the and form a government. Hidalgo was pleased with the intellegence and immediately sat about makig preparations to move on to Texas. Ryon suspected treachery and withdrew his forces but Hidalgo knowing Elisondo to be a zealous patriot, doubted not, and accordigly marched at the head of a large and wealthy concourse towards Texas his followers came not as an army but rather as friends on a visit. As he was passing a gap in a mountain between Saltillo and Monclover, at the head of his cavalcade, he found himself way laid by force of three hundred who had been placed there for his apprehension by Salcedo; he was made prisoner, hurried on to Monclover first however being forced to issue orders to his followers to surrender, which they all did, not so much by virtue of the order as from the necessity of the case, for they came on peace & were not prepared for war. Hidalgo & some of his principle followers were tied to the tails of wild mules and on the open praries Kicked to Death-This was the second & I deem all suffient ground of the condmnatn and execution of the above prisoners. The explanation was satisfactory to the army, satisfaction restored.

[Gaines refers to the assassination of Manchaca again]: When Gutaris was sent as an agent to raise assistance in the US Monshack [Menchaca] came with him; he stopped at Natchitoches while Gutaris went on to Washington–Manshack remaining behind on the nutral ground for a short time when he was bribed by the Socado, Herrera, Marcu and others to abandon the cause, which he did; but he no sooner returned to St Antonio than he was seized by these very men and beheaded—

Although there is truth in the description of vacillations between royalist and rebel, Gaines account of presumably José Felix Manchaca’s fate is in dispute. Menchaca did abandon the Gutiérrez rebels and side with royal forces and was returned to San Antonio. According to others including Texas patriot José (Joseph) Antonio Menchaca, he was tried by a military council when he returned to Bexar and was sent to Chihuahua under protective custody of Don Nemesio Salcedo where he died in prison in 1811. His crime was that he was carrying correspondence from Hidalgo, Allende and “chiefs of the Mexican revolution.” Royalist Don Juan Garcia Caso, captain of a company from Nuevo Leon under Col. Herrera, was beheaded in Montclova and his head returned to San Antonio because his name was mentioned in the correspondence carried by Menchaca, this also according to José Antonio Menchaca in later life. Later on leader of the execution squad, Antonio Delgado, was court-martialed over the incident, but acquitted. He justified his actions as retribution for the beheading and mutilation of his father and other relatives by Gov. Salcedo, for minor or incidental association with rebels.

Eighteen year old José Antonio Navarro witnessed the events which he related in his historical commentaries in the San Antonio Ledger in 1853 and in Defending Mexican Valor in Texas. He disagrees with the argument that Delgado performed the deeds because of his father’s execution as described since Delgado’s father died, as he and other relatives, on the Trinity attempting to escape from Arredondo’s forces after the defeat at Medina:

“Oh, shame of the human race! Oh disgrace for the descendants of a Christian nation! What people can coolly suffer in silence an act unparalleled in the annals of the history of San Antonio de Bexar? But we owe an impartial history to posterity, that such horrible deeds may be known to the future generations so that through their own good conduct, they may eradicate such horrible stains from our benevolent soil. One day after the slaughter, I myself saw that horde of assassins arrive with their officer, Antonio Delgado, who halted in front of the Casas Reales to inform Bernardo Gutiérrez that the fourteen victims had been dispatched. On that portentous morning, a large number of other young spectators and I stood at the door of the Casas Reales and watched Captain Delgado’s entrance into the hall. He doffed his hat in the presence of General Gutiérrez and stuttering, he uttered some words mingled with shame. He handed Gutiérrez a paper which, I believe, contained a list of those whose throats had been cut, and whose names I give below:

Spaniards (Peninsulares)

- Manuel Salcedo, Governor of Texas

- Colonel Simon de Herrera, Governor of Nuevo Leon

- Colonel Geronimo Herrera

- Captain Juan Echevarria

- Captain Francisco Pereira [Perciva]

- Lieutenant Gregorio Amador

- Lieutenant Juan Ignacio Arrambide

- Lieutenant José Goescochea

- Lieutenant Antonio Lopez

- Lieutenant José Mateos

Mexicans (Criollos)

- Captain Miguel de Areos

- Lieutenant Juan Caso

- Lieutenant Luis [de Areos]

- Ensign Francisco [de Areos]

“I myself saw the clothing and the blood-stained adornments which those tigers carried hanging from their saddle horns, boasting publicly of their crime and of having divided the spoils among themselves in shares. As I have said, it is certain that Gutiérrez received in the same Government House an account of that cruel affair, although later he disavowed taking part in the execution of the prisoners. Gutiérrez says in a manuscript which he wrote and printed in Monterrey on May 26, 1827 that he had never given the order to execute those unfortunate fourteen prisoners, but rather that a great number of citizens, who were greatly excited and angry with the Spanish governors, induced a majority of the junta to pass a formal order requiring the guard who had custody of the prisoners to hand them over immediately. The guards, Gutiérrez adds, could do no less than obey without hesitation—even though an authorization and order for it should have been prepared. Thus the prisoners under their responsibility were immediately taken out and conducted to the place where an inhuman and bloody death awaited them-a death, which was given to them without authorization and without the temporal and spiritual assistance, which the Holy Church requires. Perhaps God permitted it as a merited punishment for the inhuman cruelties, which had been committed by those unfortunate individuals. Whoever knows, or who can formulate a rough idea of the type of men of that epoch can comprehend the extreme depth of ignorance and ferocious passions of the men of those times. Whoever is informed will understand that among the Mexicans of that time, with some exceptions, there was no clear political sentiment. They did not know the importance of the words “independence and liberty” and they did not understand the reasons for the rebellion of the priest Hidalgo as other than a shout for death and a war without quarter on the gachupines, as the Spaniards were called. Thus one will readily concede and agree, as Bernardo Gutiérrez has admitted in his own way, that the band of so-called patriots “killed those fourteen victims.” But his excuse is very weak, very cowardly, and unworthy of a general who neither would nor could avoid such a scandal, much less relinquish his command upon seeing his cause blackened by a more monstrous action than could be perpetrated by a vandal chieftain. Consequently, Gutiérrez shared in the atrocity. His own dissimulation exposed him, and like Pilate he washed his hands. It was no court martial that sentenced them [Salcedo and the others], as has been erroneously stated.” (Navarro listed in his commentaries 13 victims, Yoakum in History of Texas quoting Navarro as source, also lists Ensign Francisco [de Areos]. Henry Stuart Foote in Texas and the Texans, Thrall in Pictorial History of Texas and Yoakum in History of Texas erroneously imply that former Texas governor Cordero was also executed in 1813 at or near the time described above–WLM)

Many Anglo officers and recruits were sickened and horrified by the events and a party rushed to the execution site and provided the victims with Christian burial, immediately left the cause and returned to Louisiana and points east. Although some returned, Samuel Kemper, James Gaines, Warren D.C. Hall and many others took furloughs to recover and regroup from the shock of the executions. The pleadings of Col. Miguel Menchaca and other Mexican leaders persuaded many to stay and continue to help the cause of Mexican independence through influence of the independent State of Texas under the Republican Army of the North.

Gutiérrez’s First Constitution of Texas–Deposed by José Alvaréz de Toledo. On 6 Apr 1813, Gutiérrez declared the province of Texas independent of Spain and introduced the first Constitution of Texas, which was more Centralist than Republican. Outraged by the execution of Salcedo and Herrera, loyalist forces south of the Rio Grande quickly marshaled forces and marched toward San Antonio to punish and remove the first “President and Protector of Texas.” In June, one time rebel, now royalist Lt. Col. Ignacio Elizondo marched, actually against orders, to San Antonio to engage the Republican Army (see letter below). On 16 Jun, the Republican Army under Henry Perry met and routed Elizondo’s forces, which lost 400 men killed and many prisoners, at Alazan Creek outside San Antonio. He retreated to the Rio Grande where he was reprimanded by, but joined forces with, Gen. Joaquin Arredondo, newly-appointed Commander of the recently organized Eastern and Western Divisions of the Provincias Internas, to meet the new rebel challenges. On 4 Aug 1813, President Gutiérrez was deposed by conspirators within the Republican Army which included most of the Anglo officers and recruits, who installed chief propagandist, formal naval officer and member of the Spanish Cortes from Santo Domingo, José Alvarez de Toledo.

Ignacio Elizondo Reply to Bernardo Gutiérrez Offer

In the spring of 1813, Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara, President of the first Republic of Texas, attempted to reconvert the turncoat insurgent/royalist Col. Ignacio Elizondo, who return to the royalist fold was instrumental in eventual capture of Hidalgo. Elizondo, who was in command of troops on the upper Rio Grande, was unconvinced and replied with the following letter:

To Bernardo Gutierres: With the greatest contempt I have seen thy seductive letter of the 6th April which thou hadst dispatched by Bartolo Perez. Thy absurd projects deserve no other notice than to transport my robust army and cut thee off by fire and blood, but for thy greater confusion I answer thee, that thee and thy protestants and heretics defend the cause of the Devil, and I, that of the God of Armies. Thou art excommunicated by the Holy Inquisition and by the Bishop of this Diocese, and I am a defender of religion, thou art a traitor to thy country, and I am a decided patriot. The victories which thou hast gained have been through the intrigues of heretics and traitors like thee, but thou shalt not triumph over those who may perchance die in the war. I know better than thee the condition of the Congress, and from whence, oh tyrant, hast thou learned that my king is no more! and even should he not exist, my country rules by deputies, and these same deputies in the present General Cortes made us equal to Gachupins and Creoles and granted us other favors, of which thou hast rendered thyself unworthy which might include thee if by any heroic act thou shouldst change; but I would not consent to it because I am determined that in Hell shalt thou be put, which will be thy last refuge, thy hair pulled out, thy body burnt and thy ashes scattered, and I denounce thee a coward, meet me in the field. leave the kitchens and if thou dost not I will drag thee out and thou shalt know the! man thou hast offended through thy seductive and hypocritical letter, nevertheless being a catholic I desire thy salvation. Head Quarters, Rio Grande, April 19th, 1813. Ignacio Elisondo.

Defeat of the Texas Republicans at Medina–Revenge and Decimation by Royalist Gen. Joaquin Arredondo.

Toledo renamed the movement the Republican Army of North Mexico and re-organized the army into racial units, Mexicans, Indians and Anglos, a tactical error that separated trusted comrades between ethnic groups, created suspicion and dissension in the ranks among units, a mistaken strategy to be repeated in Texas to present day. The army moved on 15 Aug to the Medina River. Mistaking a scouting party headed by Elizondo as the main royal force, Toledo gave chase across the Medina and was led head on into Arredondo’s main force. On 18 Aug, Toledo and his force of 1500 that near half were American volunteers met Gen. Arredondo’s army of 2000 to 4000 at the Battle of Medina. Four hours the Republican force, which Arredondo described in his report to Viceroy Félix María Calleja del Rey as “base and perfidious rabble commanded by vile assassins,” held with great valor and skill, but were finally routed with tremendous casualties. Some historians described the Republicans as no more than an untrained “mob”, however, Arredondo went on in his report to describe his enemy as “well-armed throughout, full of pride…and versed in military tactics.” He praised the Anglos as adept in battle by applying qualities they had learned from “traitorous Spanish soldiers.”

Motivated by vengeance over his defeat at Alazan, Col. Elizondo pursued the retreating Republicans into Bexar with a vengeance. In a panic more desperate than the Runaway Scrape of 23 years later, the Republican Army including Toledo, Henry Perry and other officers and civilians raced for safety east on El Camino Real toward the Sabine River and the Neutral Ground. Gen. Arredondo and Col. Elizondo began a systematic reign of terror and reprisal on the residents of San Antonio and Texas, which essentially decimated the meager population of Texas except for the most hardy, but also destroyed any remaining sympathy with the royal crown of Spain. Records indicate that 112 Republicans were captured at the Battle of Medina and summarily executed. About 215 were jailed upon Elizondo’s entry into Bexar. A part of Arredondo’s force under Capt. Luciano Garza took over 300 prisoners in La Bahia. Arredondo’s losses were estimated at 55 killed and 178 wounded. Arredondo imprisoned hundreds of residents of San Antonio, many of whom died of suffocation in the makeshift jails. Five hundred women and children whose male relatives were suspected of rebel sympathies were imprisoned, humiliated and enslaved. Executions on military plaza occurred daily. The heads of numerous patriots were severed and displayed in cages or on the tip of spikes on Military Plaza. In a document in the Lamar Papers, José Antonio Navarro described a “tyrant named Corporal Ribal” who terrorized the prisoners with his lash. He related:

….[the days were worse than] that could be found in the days of Marat & Robispiere, he [Arredondo] governed with absolutism over the prisoners, and when the suns rays were hidden and the dark night closed round, many officers & Soldiers met with their friend the guardian, to be treated each one of them, to the victim (woman) that he might think proper to assign them for that night upon which, each one of those monsters would saciate his lasciviousness, and then turn her over to the Guardian Acosta, to continue the day following in the work of the tortillas for the soldiers. It is due to justice however to say that there were among these prisoners many Heroines who struggled arm to arm against addressing & resisted the delivery of their persons to the commands of that infamous Jailor; this class of Heroines never would consent to stain their honor, but they had to suffer the torment of cruel & daily lashes, there are yet surviving in Bexar some of these matrons Idolaters of their own chastity; I know two of them, one of whom for having opposed herself to the iniquitous treatment of the Said Acosta, he bound and hung up a public spectacle in the same Quinta, more than of one hour stripping her even of her under clothes and leaving her nakedness an object of public gaze, Arredondo knew all that passed, and when in his court of officers any of these cruel anecdotes would be cited, a pleasant smile would close the scene…..

Property was confiscated from all but those who could prove their continuous loyalty to the Spanish crown. Col. Elizondo’s forces captured a group of families on the Trinity River and summarily executed over 100 males on the spot. Among these was Captain Antonio Delgado, the executioner of Govs. Salcedo and Herrera and their officers at Salado, who was shot on the spot along with several relatives, and his body left for the wolves and buzzards. In his commentaries in the 1850’s, José Antonio Navarro tells of a Padre Camacho who set up a confessional according to rites of the Catholic Church. When Padre Camacho elicited confession sufficient to implicate the individual with the Republican Forces, he gave a signal to the executioners. He is said to have raised his clerical habit and pointed out the wound he had suffered at the Battle of Alazan. With the words “Move on my son and suffer the penalty in the name of God, because the ball that wounded me may have come from your rifle,” he delivered the Texas patriots, who were shot in groups of 20 to 30, to the executioners.

General Arredondo made it clear that the royal crown was in control of the Sabine River border and any that crossed it would be shot on sight. According to most historians Arredondo re-established royal control of Texas so thoroughly that, in words of Felix D. Almaraz Jr., “the province was virtually depopulated save for the settlement of Bexar.” Texas was essentially reduced to its pre-Spanish mission wilderness state, the neglected frontera, hinterlands and borderlands of New Spain. Economically and in reality politically, current Texas was again reduced to a “No Man’s Land” on the western border of the USA on the Sabine River and the Rio Grande River. From the view in the east, Texas was the next frontier of opportunity, an arena in which to continue execution of the pioneering frontier spirit of political and economic freedom that began on the Atlantic coast in the second half of the 18th century. The view from south of the Rio Grande was that the Sabine River was the border of New Spain and Texas was to be protected as a buffer zone against further expansion of the USA into even the southern provinces of New Spain. Opinions by some vocal factions in the USA that the Louisiana Purchase extended to the Rio Grande River had not diminished since the territory became temporarily a part of New Spain, France and then the USA in 1803. The objectives of the resilient native Texas frontier peoples remained the same as their Anglo-American counterparts to the east—economic and political freedom with local governmental control.

Leave a Reply