Abuelos de Texas

Let Go, Let God

Fighting to tell the untold story of True Texas history.

¡Viva Texas!

Celebrating our rich family heritage and enduring spirit in Texas — from the Old World to the New — we honor centuries of faith, family, and freedom.

God Bless Texas!

Our Dedication

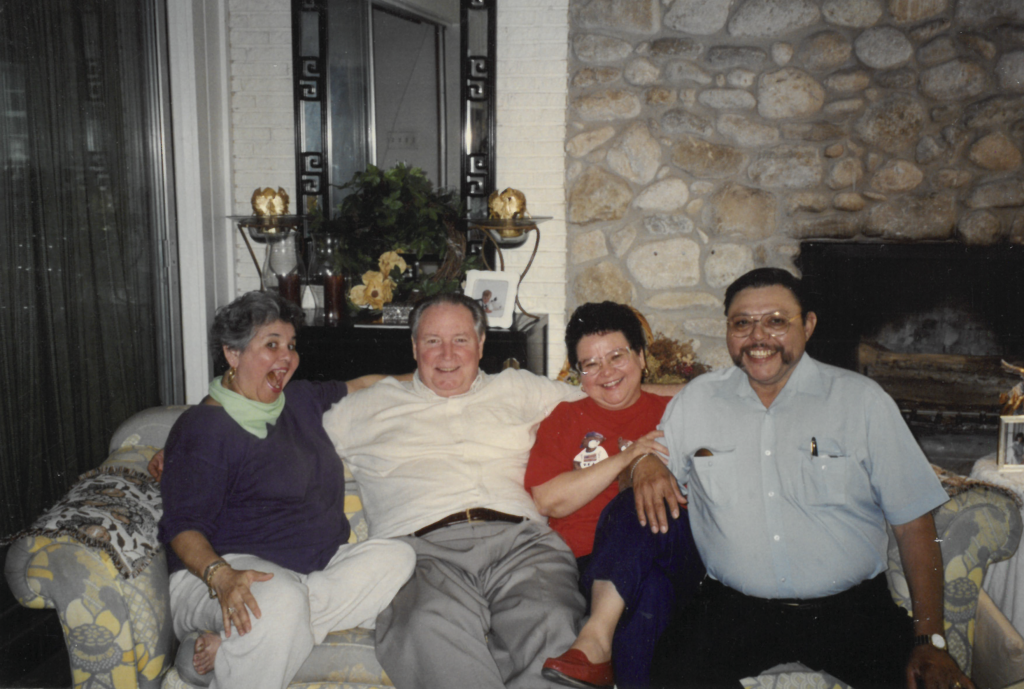

Dedicated to Elma Esparza Wright and Delfina Esparza Perez. They led their lives with love, humility, and selfless service. Elma a day care owner and Delfina a Texas history teacher, both teaching us grandchildren about our Esparza heritage.

Elma was the fun spirited, easy go lucky, life of the party who always brought cheer and joy. Delfina the studious scholar, well educated and shy history teacher who documented all the family stories and irreplaceable truths so us grandkids can continue to teach our children and our children’s children to heritage we love!

The Esparza Sisters of Brownsville, TX descend from a centuries-old lineage rooted in limpieza de sangre (“cleanliness of blood”), a term used in Spain after the 781-year Reconquista. In the New World, their ancestors intermarried with Indigenous nobility — most notably when Lope Ruiz de Esparza married Francisca “Ana” de Gábadi Navarro y Moctezuma, granddaughter of Emperor Moctezuma II.

This union helped form the early mestizo identity — half Spaniard, half Aztec — the foundation of modern Mexican heritage. Many South Texas Tejano families share this deep & rich ancestry, descending from Moctezuma II and the Famous Spanish conquistadors: Colombus, Cortés, Coronado, and even royal lines through Alonso de Estrada, son of King Ferdinand II.

God Bless The Esparza Sisters.

Information based on Delfina Esparza Pérez’s lifelong (50+ years) genealogy and family history research.

Our People

Our life stories are carried through the lives of those who came before us and those who will come after us. From the Basque valleys of Spain to the northern frontier of New Spain, our ancestors were leaders, settlers, ranchers, soldiers, builders of community, and most importantly missionaries of The Gospel. This site honors their lives and preserves their legacies — ensuring that their history, faith, and enduring spirit continue to inspire our future generations.

Glory be to God that we know our roots, so we may bear good fruits.

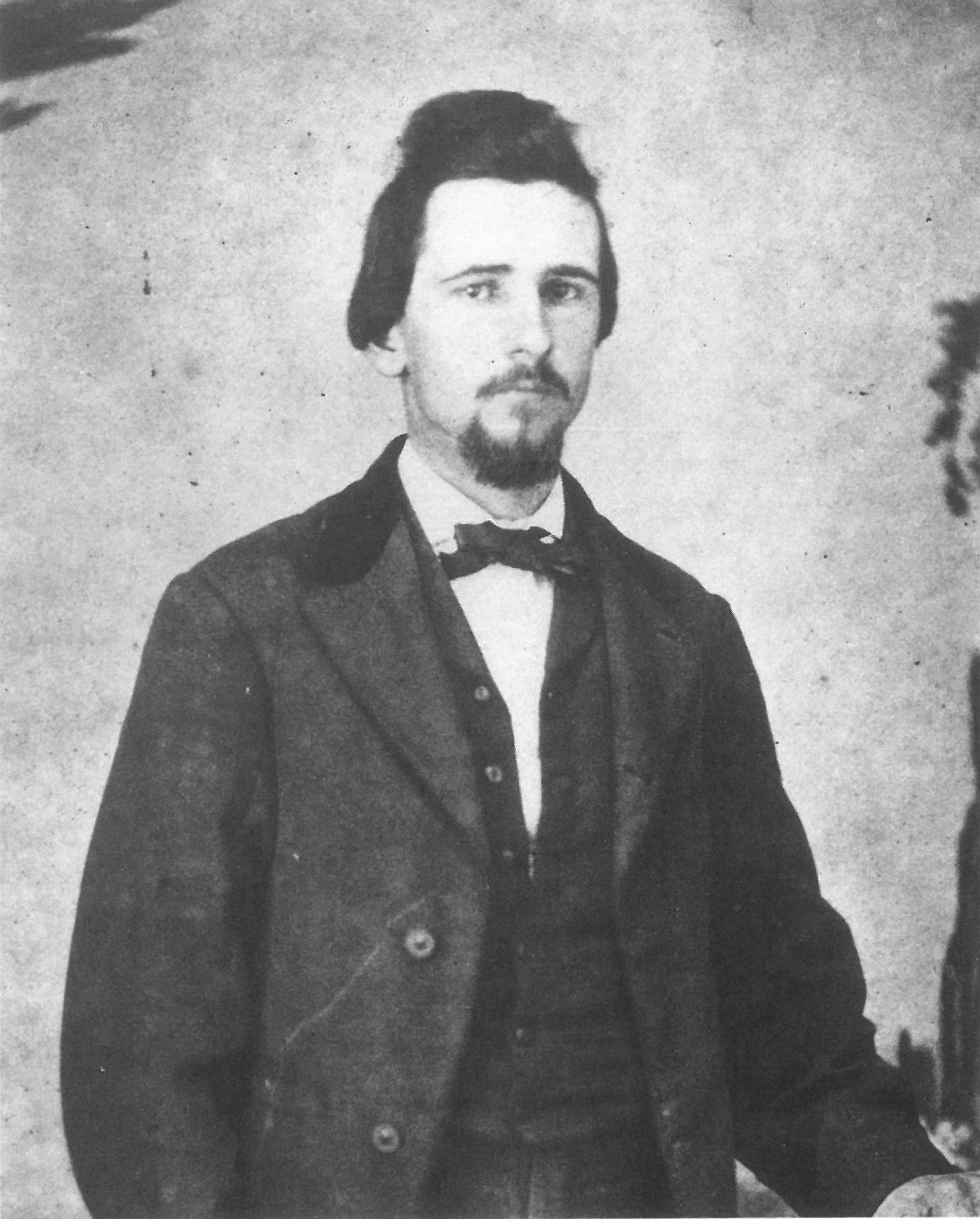

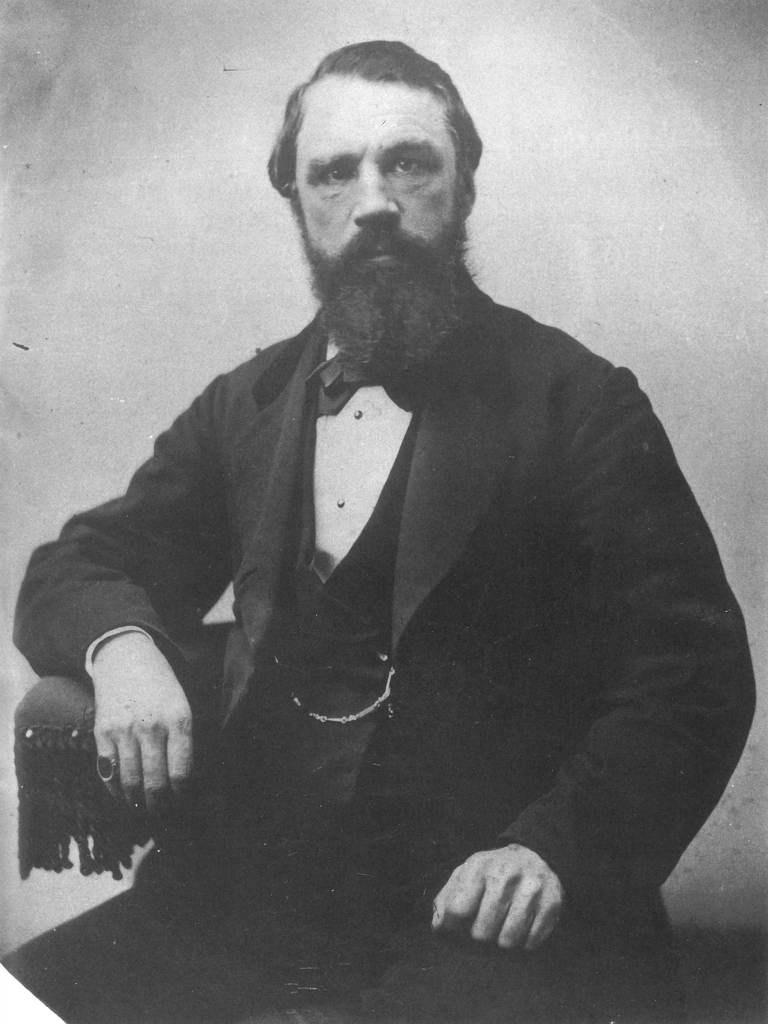

The Alamos Last Defender & Only Christian Burial

José María “Gregorio” Esparza

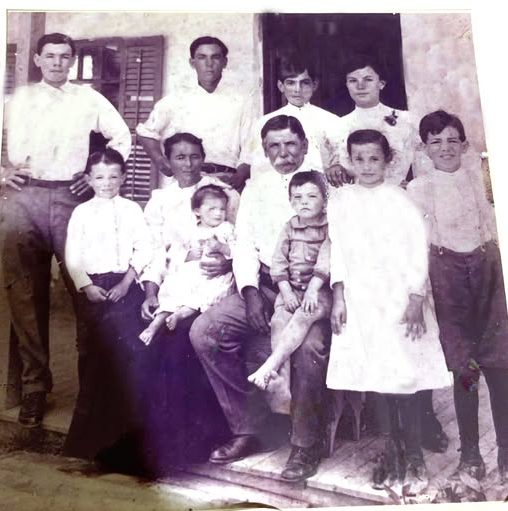

Cavazos-Reyes-Esparza-de la Garza Family

La Encantada “Enchanted” Ranch, Espíritu Santo “Holy Spirit” Land Grant circa 1895

The Esparza Sisters Grandmother & Great Grandmother

Bottom: Virginia Cavazos Reyes Esparza (1875-1967) | María Inocente “Inocencia” de la Garza Cavazos Reyes (1846–1935), Esparza Sisters Great Grandmother | Cruz Cavazos Reyes Vera (1885-1925) | Refugia Cavazos Reyes (1882–1936) | Cecilia Cavazos Reyes (1876–1945)

Not Pictured: José Antonio Guillermo Reyes (1845-1920), Esparza Sisters Great Grandfather

Cavazos-Esparza Family at La Encantada Ranch

Maria Cavazos Esparza & Antonio Villarreal Esparza circa 1910

The Esparza Sisters Great Grandparents

Bottom: Ramon Reyes Esparza (1902-1988) | Maria Hilaria Cavazos Reyes Esparza (1870-1945) holding Fidela “Fifi” Esparza (1908-1994) | Antonio Garcia Esparza (1865-1935), Esparza Sister Grandfather, holding Enrique “Henry” Esparza (1906-1980) | Francisca “Panchita” Reyes Esparza (1901-1980) | Guillermo “Willie” Esparza (1898-1935)

Not Picture: Not yet born Samuel Cavazos Esparza, the Esparza sisters father

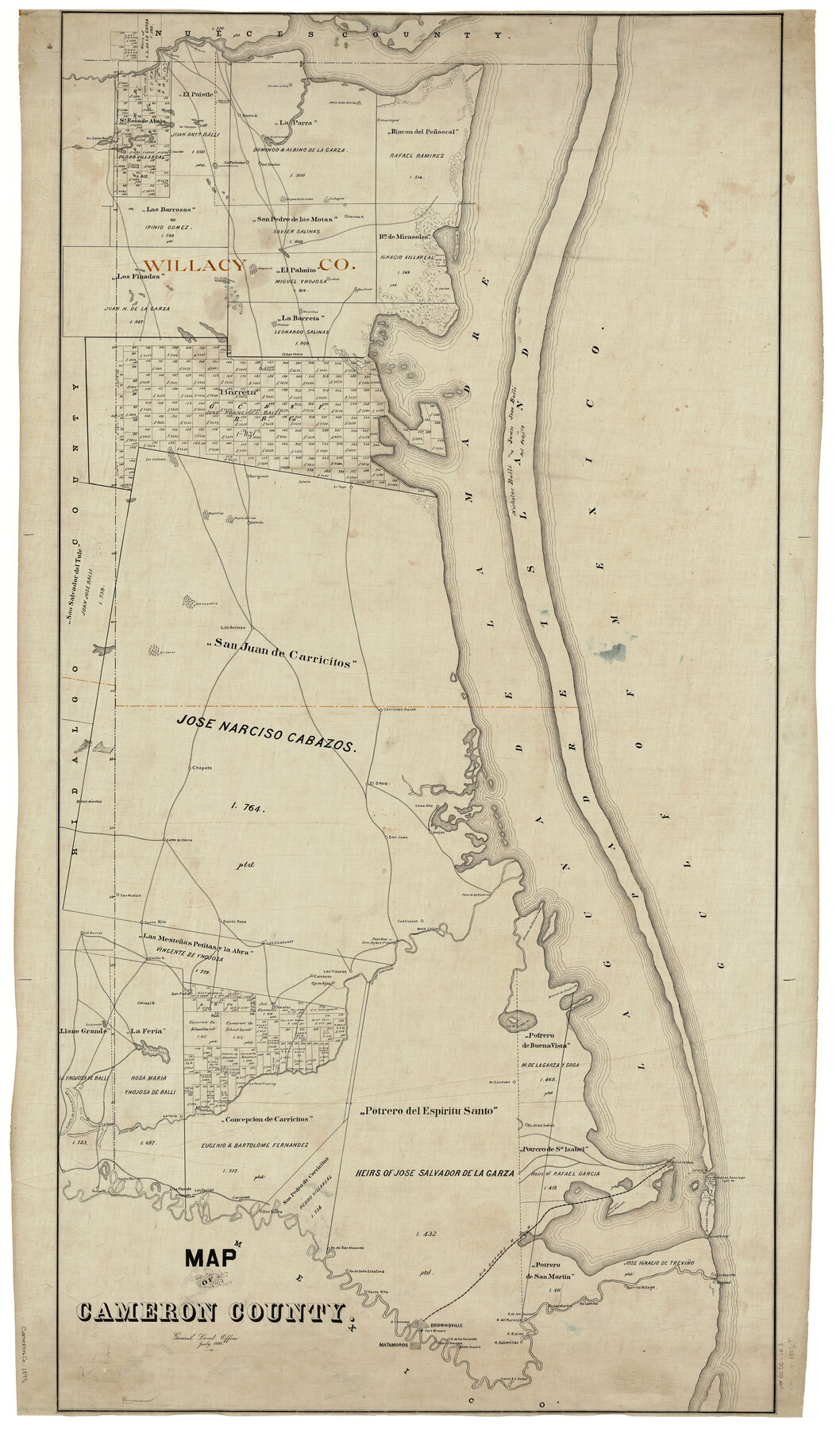

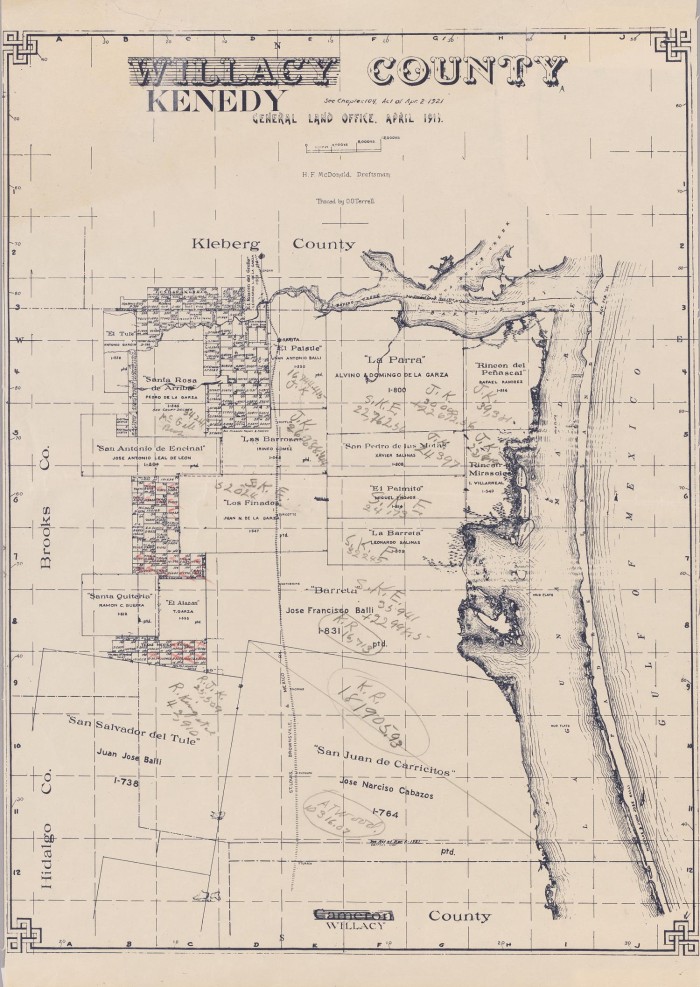

The family above are descendants of Captain Tomas Sanchez de la Barrera y de la Garza (1709–1796), Jose Salvador de la Garza Villarreal Falcón, and Jose Narciso Cavazos Gonzalez (1750–1802) (spelled “Cabazos” on the map below). These families were deeply connected through more than a century of intermarriage with other original landowners and ranching families of Texas, reflecting common practice and traditions among Texas hispanic settlers.

Such concept was rooted in a old Spanish tradition called “limpieza de sangre” (“cleanliness of blood”), which historically referred to maintaining Christian lineage after Spain’s centuries-long (781 year) Reconquista war against Moorish invaders and rule – ending in 1492 with the fall of Granda and the discovery of America. It is possible and debated the Basques of northern Spain had know of and been fishing these NewFoundLand waters before Christopher Columbus’s (Cristóbal Colón) official discovery but kept it a trade secret as their bustling industry helped fund the war against the Moors and reclaim Spains united monarchy – leading to the Conquistador era and the Spanish Empire.

Over time, Spanish settlers in the New World, Now Americas, often intermarried with Indigenous peoples, including descendants of the Aztec nobility such as Emperor Montezuma II. This blending of cultures gave rise to the mestizo identity “mixed blood” — half Spaniard, half Indian — which today forms the core of Mexican heritage. Many Tejanos in Texas today can trace their lineage to Emperor Montezuma II and Spanish conquistadors including Christopher Columbus, Hernan Cortés, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, and even royal lines through Alonso de Estrada, son of King Ferdinand II.

Family Land Grants by Kings of Spain

1792 San Juan de Carricitos Grant 601,000 acres | 1781 Espíritu Santo Grant 285,000 acres

From 1880-1920 the Esparza’s & Cavazo’s went from 950,000+ acres to a 520 sqft home in Brownsville for a family of seven.

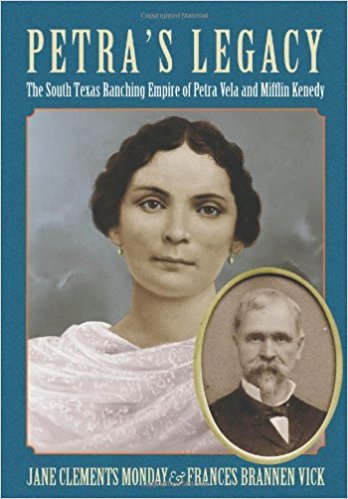

Known as “The Bloody Border” this South Texas region known last the “Nueces Strip” – between the Nueces and the Rio Grande rivers – is home to some of the best American history. These two land grant ranches were the setting for the first two battles of the Mexican-American War (1846–1848) and the final battle of the Civil War (May 13, 1865). During the Civil war, Brownsville’s was known as “The Confederates Backdoor” as the cattle barons – Charles Stillman, Richard King, Mifflin Kenedy – were smuggling slave cotton around the Union’s naval brigade in the Gulf and shipping it though Matamoros, Mexico back to the Union Army in New York to be paid in Gold Bars. So much cotton was pouring into Brownsville that it caught the nickname “Cotton Town,” today Brownsville is home to Starbase.

In the early 20th century (1910–1920), this region witnessed La Matanza and Hora de Sangre (“The Massacre” and “Hour of Blood”), a tragic period marked by lynchings, mass murders, forced displacement of original ranch owners, burning of homes, and Mexican labor camps – largely at the hands of law enforcement, The Texas Rangers. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson sent more than 110,000 U.S. troops to be stationed along the Texas–Mexico border in response to escalating violence and instability during the Mexican Revolution.

From Nueces to Kenedy & Kleberg Counties

- Nueces County was created in 1846 from part of San Patricio County, covering the vast region between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. At the time, it was enormous—stretching across land that would eventually be divided into several future counties.

- Cameron County followed in 1848, carved from the southern portion of Nueces County along the Rio Grande. This new county included Brownsville and the lower Rio Grande Valley.

- Willacy County was established in 1911 from parts of Cameron and Hidalgo Counties. Its original boundaries were much larger than today, encompassing the territory that would later become Kenedy County.

- Kleberg County was created in 1913 from the southern part of Nueces County. This region included the rapidly expanding King Ranch, which had grown into one of the largest ranching empires in the United States.

- Kenedy County was last in 1921, separated from Willacy County, taking with it much of the sparsely populated ranch land—including sections of the historic San Juan de Carricitos Grant.

Maps of the Historic Spanish Land Grants of South Texas

These map highlight the historic San Juan de Carricitos Grant (“Saint John of the Little Reeds,” named for its wetland prairie grass) and the Portero del Espíritu Santo Grant (“Pasture of the Holy Spirit”), along with other original family holdings such as those of the Villarreal, Trevino, Ballí, García, and Hinojosa. These vast open ranges, originally called the Wild Horse Desert for its legendary, uncountable, and free ranging herds of mustangs and cattle introduced by Tejano settlers — are central to Texas history.

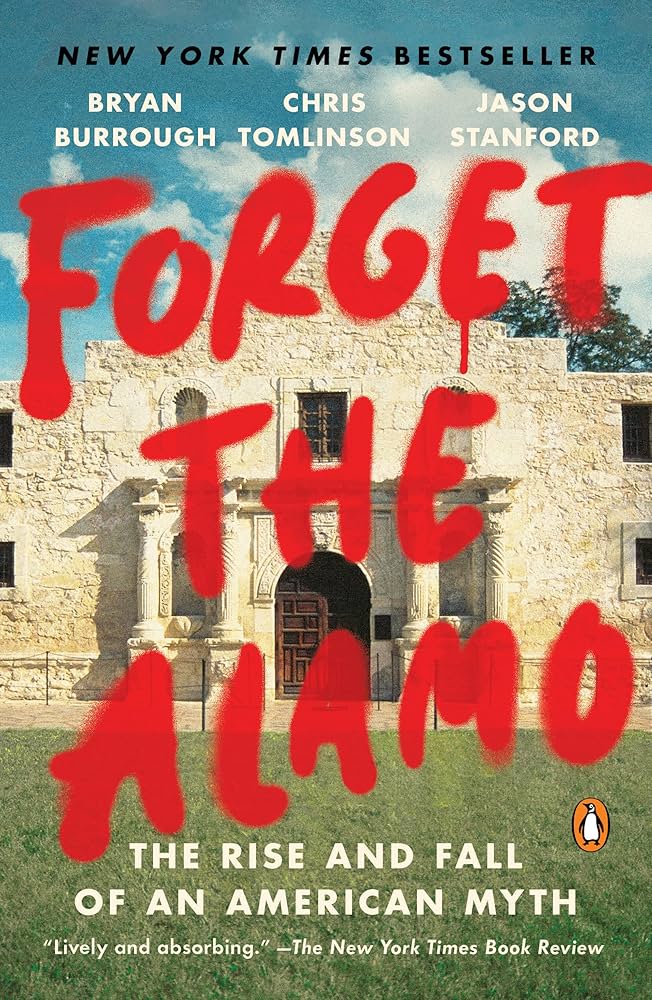

The lands that now make up the King Ranch and Kenedy Ranch—today among the largest cattle, farming, and oil empires in the United States—were once Tejano-owned ranching estates protected under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848). Their transformation into Anglo-American dynasties reveals a deeper conflict between the ideals of the United States and the lived reality along the South Texas frontier.

America’s founding philosophy rested on the sanctity of property: John Locke wrote that “Lives, Liberties, and Estates… I call by the general Name, Property,” a principle that shaped the Thomas Jefferson and the Constitution itself. John Adams insisted, “Property must be secured, or liberty cannot exist,” while James Madison declared that the very purpose of government was “to protect property of every sort.” Even George Washington affirmed that “private property and freedom are inseparable.”

Yet between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, these promises unraveled. Despite treaty guarantees, Tejano ranches—including historic Spanish and Mexican land grants—were slowly stripped away through legal manipulation, violence, artificial debt coercion, and systemic discrimination. The lofty ideals of America’s founders stood in stark contrast to the reality experienced by the very families who had built this region long before U.S. statehood.

The Sinking of The Anson & Tejano Titles

In 1850, the Anson Jones steamship sank off the Texas gulf coast while carrying a trunk filled with the states land grant commission reports including the original Spanish and Mexican land grant titles. The Anson’s Captain: Captain King.

This States commission had been appointed by the State of Texas after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) to verify and confirm land grants records. James B. Miller collected the Land Grant documents in Brownsville and was to headed to Austin for his review. “Miller decided to make the voyage from Port Isabel to Galveston on the steamer Anson before going overland to Austin. Two days out, the Anson sank fifteen miles from Matagorda. Miller lost his trunk, the original titles, and about $800 in fees from claimants.”

Leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of tomorrow.

“Remember the days of long ago; think about the generation’s past. Ask your father, and he will inform you. Inquire of your elders, and they will tell you.”

Deuteronomy 32:7

Learn True Texas History

WATCH TRUE TEXAS HISTORY!

“Porvenir, Texas” is a 2019 documentary that explores the 1918 massacre & land grab in the border town of Porvenir, TX

Our Blog

Join 900+ subscribers

Stay in the loop with everything you need to know.